The Therapeutic Value of Art |

| By Lauren Slater |

|

With many of us in quarantine and perhaps single isolation, for some, our mental health is becoming a main feature discussed across social media and news channels, deciphering ways in which we can combat loneliness and depression. Management techniques have included exercising, virtual communication, and maintaining structure within your daily routines. Alongside this, people have turned to painting, drawing, and other forms of creative outlets. With a rise in research into the relationship between physical and mental wellbeing, and the creative arts, this feature looks at the therapeutic value of art and its contribution at a time of global pandemic. |

|

The role of the museum/art gallery within society today, has become a symbol of reflection and peace, whether displaying contemporary works or readdressing the past through more politically attuned pieces. Likewise, the role of art has grown to encompass therapeutic values to help and maintain physical and mental wellness, in conjunction with this. The Phillips Collection (Washington D.C.), founded in 1921, demonstrates the shift in the role of the art gallery. Established as a result of the Spanish Influenza Pandemic in 1918, the museum was founded by Duncan Phillips to pay homage to his father and brother, who both fell ill, and later died from the flu. The Phillips Collection was then to become a museum ‘for the people’, in which visitors could find solace. This ethos of the museum, has continued to work into the modern day where last year, an Annual Artists of Conscience Forum was held, focused on engaging veterans with art therapy to help deal with post-war mental health challenges. Such programmes have since been supported by the publishing of the World Health Organisation’s inquiry ‘What is the evidence on the role of the arts in improving health and well-being?’, in 2019. In the inquiry, Daisy Fancourt and Saoirse Finn address this notion by stating, ‘[t]he arts are being used to help military veterans to engage with health issues, for example […] art appreciation classes for veterans with severe mental illness in recovery centres’.[i] In this way, through the exploration of forms, colours, and textures the mind is focused purely on the art, aiding towards complete mindfulness. Alain De Botton, author of Art as Therapy, poignantly expresses this. Art ‘is a vehicle through which we can do such things as recover hope, dignify suffering, develop empathy, laugh, wonder, nurture a sense of communion with others and regain a sense of justice and political idealism.’[ii]

|

|

The acting of creating has proven to play a pivotal part in helping people deal with emotions of self-doubt and anxiety. In their inquiry, The World Health Organisation noted activities including, ‘listening to music […] art and visiting cultural sites are all associated with stress management and prevention, including lower levels of biological stress in daily life and lower daily anxiety.’[iii] Such interventions have proved significant for Gallery Different’s resident artist, Matt Lambert. From a young age, Lambert has been no stranger to the struggles of mental health and anxiety impinging on his life, where fear and worry have built up a particular and omnipotent dialect. Lambert values the importance of painting within his daily routine seeing it as vital to his dealings with spells of anxiety. When asked about his work, Lambert states, ‘it is not that I have created work specifically about my mental health, its more that the process of doing something I love, understand and feel secure with has given me a means to positively direct my attention when I’ve really been struggling.’ Interestingly, Matt Lambert’s portfolio of works addresses the plight of the human condition in many subtle and tender ways.

|

|

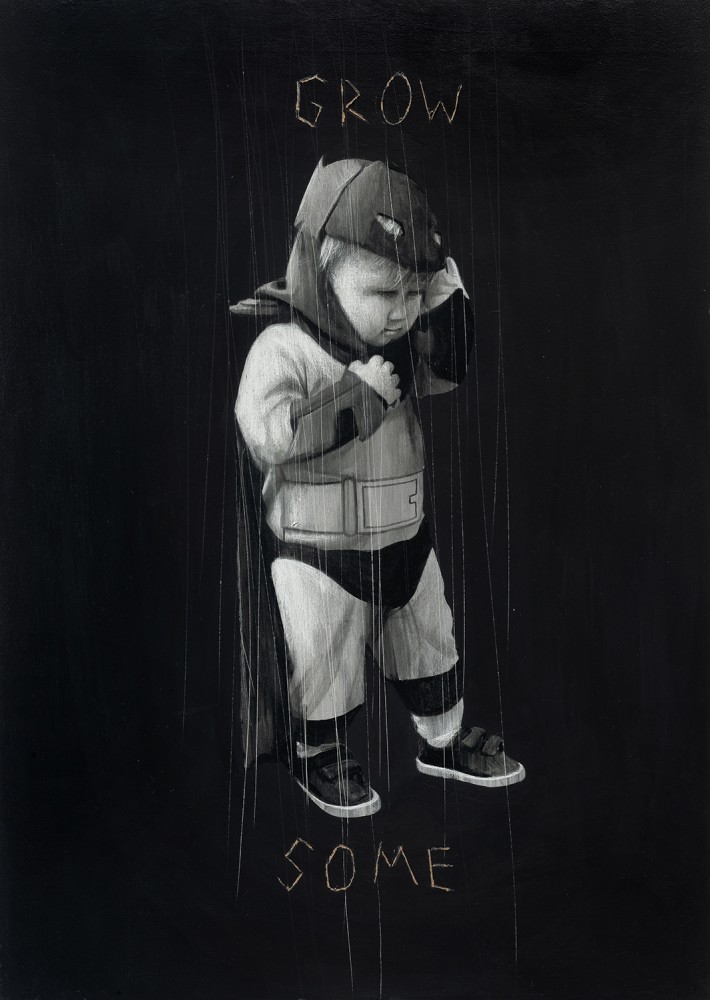

Of particular prevalence are Lambert’s Superhero Series, which pay considerable attention to the theme of masks. The subjects, all depicted in the forms of toddlers wearing superhero masks and costumes, are painted displaying an air of heroism. On the contrary, the titles suggest otherwise. Produced in 2019, Lambert’s Grow Some is demonstrable of this. The monochrome palette focuses particular attention on the young boy, stood in the centre of the work, with ‘Grow Some’, etched above and below his figure, almost enshrouding him. The boy’s averted gaze and releasing of his mask are emblematic of his succumbing, with his posture wilted by pressure. The term ‘Grow Some’, commonly associated with maturing and confidence, most notably in men, suggests forcing one out of their comfort zone, and into a world of toxic masculinity. The overt reference to grown men suggests that behind all their costume and front, many still feel the vulnerability of a young boy, and that there is a sentiment one must ‘act like a man’ in order to fit in. Matt Lambert’s Best Laid Plans (2019), is also symptomatic of this, in which the subject has shed his superhero costume in favour of his true identity.

Matt Lambert, Grow Some (2019) - Acrylic on board |

|

Alongside the positive impacts of art production on mental and physical health, the process of seeing art has also been noted to have considerable benefits. Art has the ability to access ‘some of the most advanced processes of human intuitive analysis and expressivity and a key form of aesthetic appreciation is through embodied cognition, the ability to project oneself as an agent in the depicted scene’[iv], as stated by Christopher Tyler, Director of the Smith-Kettlewell Brain Imaging Center. Embodied cognition, Tyler goes on to explain is ‘the sense of drawing you in and making you really feel the quality of paintings.’[v] This can be felt through the work of contemporary artist Gwen Joy Royston. Royston’s abstract paintings maintain particular focus on the marks, forms and colours that inhabit the canvas. Created in 2018, Royston’s Hang Up demonstrates clear and concise strokes yet amongst them, the delicate run of the purple is spontaneous and accidental. This is a projection of both Royston, and our own lives in which control and chaos co-exist. Such strokes encourage the viewer to think more deeply about their own life and where, despite there being unjustified chaos and accidents, we can still regain power. Whilst looking at the canvas, our minds are immersed with the merging colours and lines and the more precise motions. Here, we spend time contemplating the process and appreciating its value, allowing us to become side tracked from the encroaching every day anxieties.

Gwen Joy Royston, Hang Up (2018) - Oil on canvas |

|

|

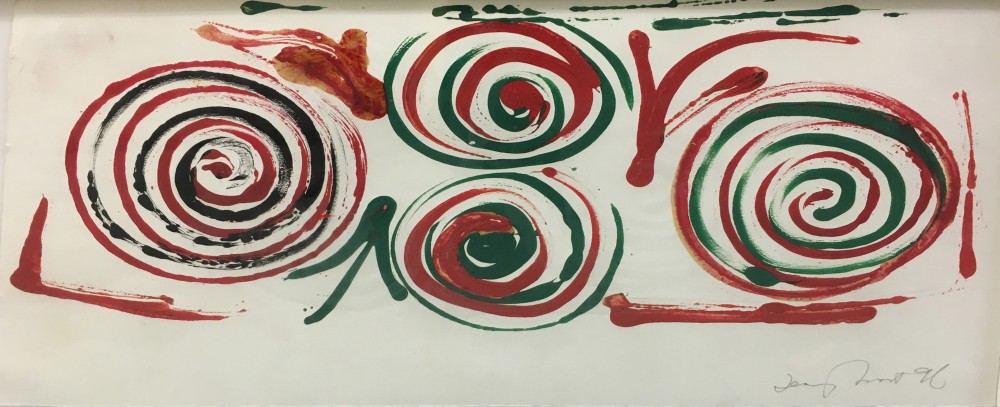

A hugely significant inquiry, in 2017 by King’s College London, explored the relationship shared between the arts, and human health/wellbeing. The report found that first-hand benefits of art include stimulating imagination and reflection, encouraging greater dialogue with oneself and altering perspectives. The inquiry continued to explore the many functions of art, including ‘a place of safety and freedom from judgement […] increase control over life circumstances; inspire change and growth [and] engender a sense of belonging […] [promoting] healing.’[vi] This has similarly been addressed in the World Health Organisation inquiry where they found Doctors’ surgeries with art on the walls, saw patients had reduced anxiety, increased satisfaction and improved communication between patient and doctor. The work of artists such as post-war contemporary Sir Terry Frost supports this. Like Royston, Frost’s work primarily deals with an expansive colour palette, that is also symptomatic of overcoming incredibly difficult circumstances. Unfortunately in June 1941 at the height of World War II, serving with the commandos in Crete, Frost was captured and transported across various prisoner of war camps. When later relaying these memories, Frost recalls the years as a ‘tremendous spiritual experience, a more aware or heightened perception during starvation.’[vii] Despite all the challenges faced during the war, the great magnitude of colours Frost utilised post-war are illustrative of this hope that lay beyond the current circumstances. Sir Terry Frost’s spirals, bold in colour and stroke, set against a white background again highlight this. The sacred symbol of the spiral, representing the journey and evolution of life are optimistic. The red and green of the spirals are entwined, showing how nature and danger fuse together and coexist with one another. Ultimately, however, as the spiral does, so must the journey come to an end.

|

|

This feature has aimed to address some of the many benefits that the visual arts can have on our physical and mental health. Although the focus has primarily been on the visual arts, there are great resources that shed light on other creative forms such as theatre, music and dance. Through creation, appreciation and display art can help boost morale, empower us and enable us to become more reflective of ourselves, ‘[accessing] a range of emotions, including anguish, crisis and pain’.[viii] Despite the closure of museums and galleries nationally, exhibitions have made their way onto virtual spaces and now with heightened image resolutions, you can enjoy the museum space within the comforts of your own home. Be reminded that everyday creativity, as explored by King’s College London ‘which may be undertaken alone or in company […] has an immense contribution to make to happy, healthy lives without necessarily having a connection to health or social care.’[ix] During this time, your happiness is paramount. Stay safe, stay well, stay positive. |

| References: |

|

[i] D., Fancourt and Finn, S., What is the evidence on the role of the arts in improving health and well-being?, The World Health Organisation (2019) https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/329834/9789289054553-eng.pdf p.21

[ii] A., de Botton, Alain de Botton’s guide to art as therapy, The Guardian (2014) https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/jan/02/alain-de-botton-guide-art-therapy

[iii] D., Fancourt and Finn, S., What is the evidence on the role of the arts in improving health and well-being? The World Health Organisation (2019) https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/329834/9789289054553-eng.pdf p.23

[iv] C., Tyler, How Engaging With Art Affects the Human Brain (2013) https://www.aaas.org/news/how-engaging-art-affects-human-brain

[v] C., Tyler, How Engaging With Art Affects the Human Brain (2013) https://www.aaas.org/news/how-engaging-art-affects-human-brain

[vi] King’s College London, Creative Health: The Arts for Health and Wellbeing (2017) https://www.artshealthandwellbeing.org.uk/appg-inquiry/Publications/Creative_Health_Inquiry_Report_2017_-_Second_Edition.pdf p.20

[vii] Wikipedia, found in The Times, Obituary: Sir Terry Frost (2003) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Terry_Frost

[viii] King’s College London, Creative Health: The Arts for Health and Wellbeing (2017) https://www.artshealthandwellbeing.org.uk/appg-inquiry/Publications/Creative_Health_Inquiry_Report_2017_-_Second_Edition.pdf p.20

[ix] King’s College London, Creative Health: The Arts for Health and Wellbeing (2017) https://www.artshealthandwellbeing.org.uk/appg-inquiry/Publications/Creative_Health_Inquiry_Report_2017_-_Second_Edition.pdf p.21 |